5 min read

Metrics can provide teams with insights and evidence where things are taking longer, are causing friction, and need attention to improve the flow of work. Focus on improving the most significant bottlenecks first.

I recently observed a discussion between an Agile team leader and a product owner. The Agile leader was worried about the business pressuring the product owner for delivery, who then used metrics to shift blame onto the team. Some of our Agile leaders see this product owner as authoritative and controlling. The product owner could benefit from dedicating more time to grasp agile delivery, team structure, roles, responsibilities, and the importance of metrics and team cohesion. However, that’s a separate matter.

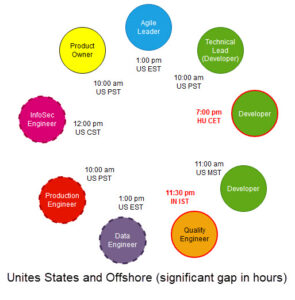

After reviewing Flow Velocity, the product owner challenged the team’s work estimate, insinuating that the team’s velocity was not good enough and needed improvement. I sensed that this perturbed the agile leader. Post-discussion, I conversed with the agile leader, acknowledging the product owner’s valid points on velocity improvement. Every team should want to improve velocity. However, I noted the lack of concrete evidence behind the product owner’s critique. What data supported his assessment of the team’s efficiency? His comment seemed biased and lacked a factual basis. This interaction prompted me to create this post.

Introduction: The Foundation of Game-Changing Agile Practices

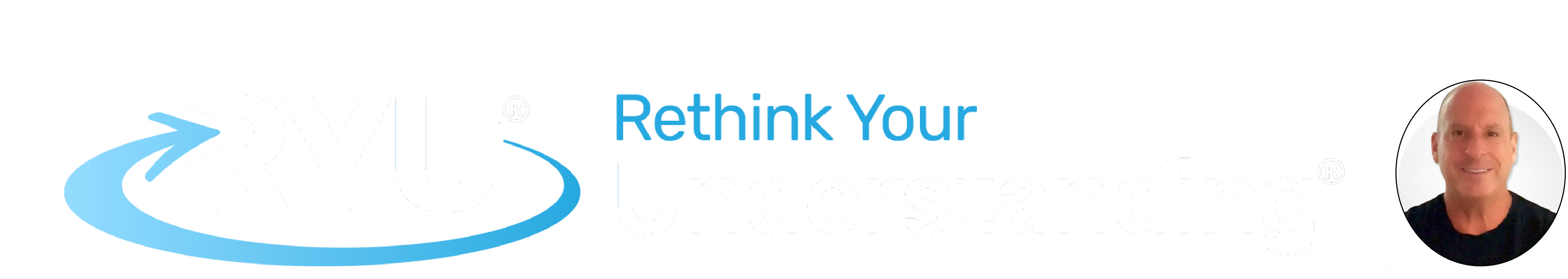

A strong focus on value stream management, flow metrics, and team structures are at the core of successful digital product delivery. When implemented across the system, these components bring significant changes that reshape agile software development. Over the past six years, my journey has closely involved these frameworks and practices, influencing the structure of my departments. This experience and a culture rooted in modern agile principles emphasize a fundamental belief: prioritizing people, processes, and tools in that specific order.

This philosophy guides our strategy and reflects how we operate. Modern agile principles help us navigate digital product delivery complexities, highlighting the vital role of human elements in achieving success. Our blend of advanced practices and dedication to agile values is the foundation for creating environments where teams excel, innovate, and provide exceptional value.

During a conference presentation last year, I showcased this approach as one of the most promising methods I’ve encountered in my over twenty years in software engineering and delivery. This synergy will help us, and you outperform other digital delivery teams stuck in outdated team structures and practices.

Delving into the intricacies of DORA, Flow Metrics, and Team Health metrics, it’s crucial to recognize that these tools and methods serve a broader mission. They aren’t just goals but pathways to enhance agility, efficiency, and team morale. With this fundamental insight, let’s dive into how a well-rounded metric strategy can empower teams, manage risks, and foster the constant improvement central to agile excellence.

Ensuring Team Metrics Empower, Not Impair

In pursuing agile excellence, embracing modern metrics like DORA, Flow Metrics, and Team Health metrics establishes a robust framework to evaluate and enhance software development practices. Yet, addressing the potential risks linked to the misapplication of these metrics is crucial. Drawing from 24 years of experience, it’s evident that without careful oversight and a profound grasp of their purpose, businesses could exploit these metrics, leading to gamification and focusing on manipulating metrics rather than genuine improvement.

Metrics are essential tools in the arsenal of engineering leaders and teams, providing necessary insights that guide teams toward continuous improvement. The value of these metrics lies not in their ability to compare teams or individuals but in their capacity to provide insights and feedback and foster growth and efficiency within the context of each team’s unique challenges and objectives (bottlenecks or friction). Also, one metric does not tell the story. You should rarely assess a team’s performance on one metric.

Understanding and Communication

Utilizing metrics effectively starts with engaging engineering teams in defining, communicating, and comprehending these metrics. This strategy ensures that teams grasp the significance of each metric about their processes and goals. It underscores the value of teams and recognizes that proficient delivery teams are crucial for successful software development. Embracing these metrics enables teams to identify bottlenecks and obstacles within their team, practices, and workflow.

Context and Comparison

Work context dramatically affects how metric values are interpreted and standardized. Comparing teams is dangerous. Comparing teams without factoring in their unique work elements and context can result in inaccurate productivity assessments. The key lies in evaluating a team based on its previous performance, tracking progress, and pinpointing improvement areas within their context.

Mitigating Risks: Gamification and Weaponization

The danger of metrics being misused by the business and turning team focus to gamification is significant and harmful. When teams worry about metrics being turned against them, their attention moves from getting better to just following rules. This worry can result in manipulating metrics, where teams try to beat the system to boost their stats without improving their productivity or the quality of their work.

Ownership versus Compliance

Separating business conversations from team conversations about metrics is crucial to mitigate these risks. Teams must feel ownership over their metrics, viewing them as valuable feedback mechanisms that align with their goals and aspirations. This sense of ownership encourages teams to care about their metrics, using them to identify bottlenecks, improve processes, and enhance delivery.

The Example of Velocity

I spoke with one delivery team member regarding velocity, or flow velocity. This conversation was a poignant example of how metrics can be gamed. Teams may break down tasks into smaller units to artificially inflate their velocity without necessarily delivering more value. We want teams to break down work into the smallest value possible. But this team’s manipulation to improve velocity underscores the need for a nuanced approach to metrics that prioritizes genuine improvement and meaningful output over numerical targets.

Conclusion

By strategically harnessing tools like DORA, Flow Metrics, Team Experience, and engagement metrics, focusing on empowerment and thoughtful metrics management, teams can revolutionize their path to improvement and agile excellence. Embrace a culture where metrics drive team feedback, insights, and growth, propelling your organization toward continuous improvement, efficiency, and improved team performance. Keeping team metrics conversations separate from business and team-level discussions uplifts software delivery and can sustain team commitment, motivation, and dedication to improvement. When teams unlock the power of metrics for enhanced efficiency and well-being, watch the separate business conversations around the same metrics naturally align.

Poking Holes

I invite your perspective to analyze this post further – whether by invalidating specific points or affirming others. What are your thoughts?.

Let’s talk: phil.clark@rethinkyourunderstanding.

Related Posts

- Mitigating Metric Misuse: Preventing the Misuse of Metrics and Prioritizing Outcomes Over Outputs. June 21, 2023.

- Finally, Metrics That Help: Boosting Productivity Through Improved Team Experience, Flow, and Bottlenecks. December 29, 2022.

- Developer Experience: The Power of Sentiment Metrics in Building a TeamX Culture. June 18, 2023.